Unlike modern printing, whereby an image is digitally scanned and sent to an offset press or laser printer, early-to-mid 1900’s letterpress printing was a very laborious task, involving many steps. In fact, the process hadn’t changed all that much in the 500 years since Johannes Guttenberg developed movable type and a printing press in the western hemisphere in the year 1440 AD.

Attempting to replicate a process long abandoned can be challenging to say the least. Gone are the Linotype typesetting machines, the letterpress newsprint presses, the craftsmen and artisans that did everything by hand.

Remnants of those processes do exist, but sparingly, and only in niche industries or museums. There are for example, large bellowed cameras in existence, but many of the films and retouching materials simply aren’t made anymore. Letterpress plates, which were made using zinc (now deemed not environmently friendly) are now made of magnesium, the closest alternative – or even polymer plastic.

To execute a unique project like this one requires not only persistence and tenacity, and a deep passion and respect for traditional printing, but also an immense number of hours and the help of very talented and experienced craftsmen.

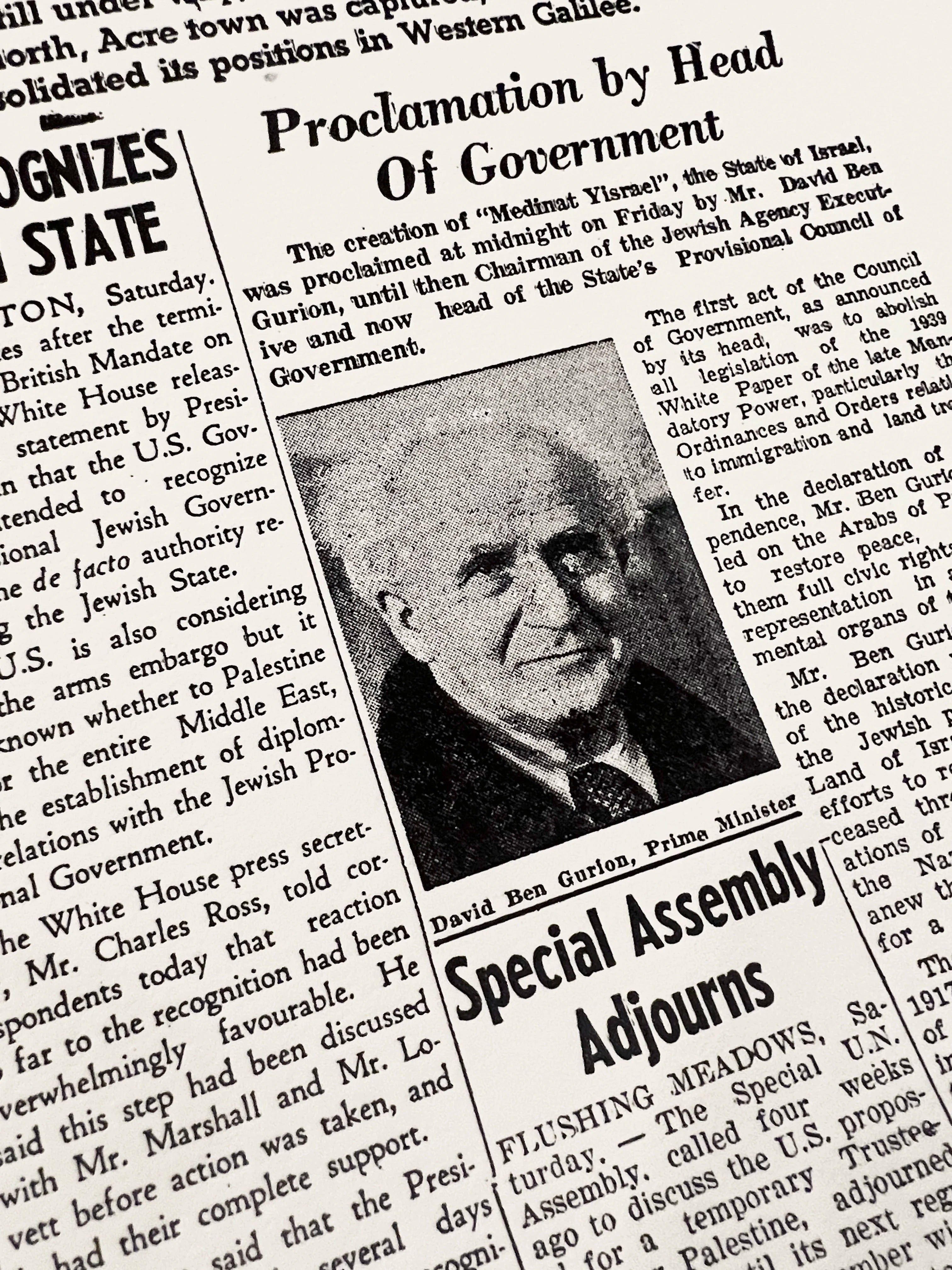

It starts with careful white-glove handling of the original newsprint, which is naturally quite fragile. That is placed in a glass frame and photographed on a piece of 20” x 24” film which is then chemically developed. Several tests are made using different exposures to find the perfect balance between maintaining the fine details of the typography and avoiding specks in the newsprint.

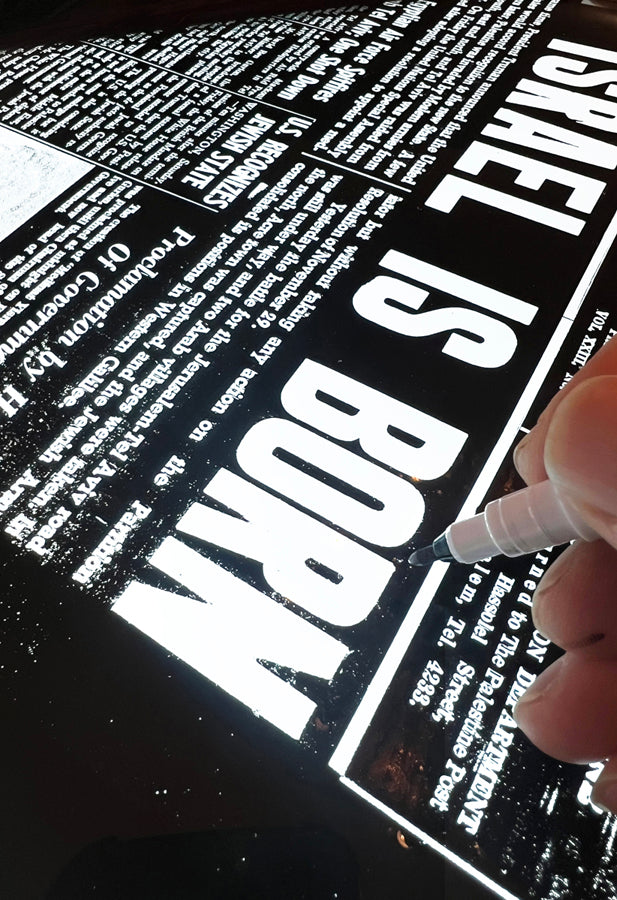

The negatives are examined on a glass light table, with special attention given to the halftones (photos made up of thousands of tiny dots). Hunched over the table, many painstaking hours are spent opaquing out all the unwanted specks and dirt.

The cleaned-up negative is then placed in a glass vacuum frame, through which a large sheet of specially-treated magnesium is exposed to ultraviolet light in a darkroom. This process hardens all the areas of the plate where the imagery is.

The sheet of metal is bleached and cleaned, and then dipped into a huge steel tank where it is spun, bathed, and sprayed with acid. The softer areas (everything but the type that needs to print) are thereby etched away.

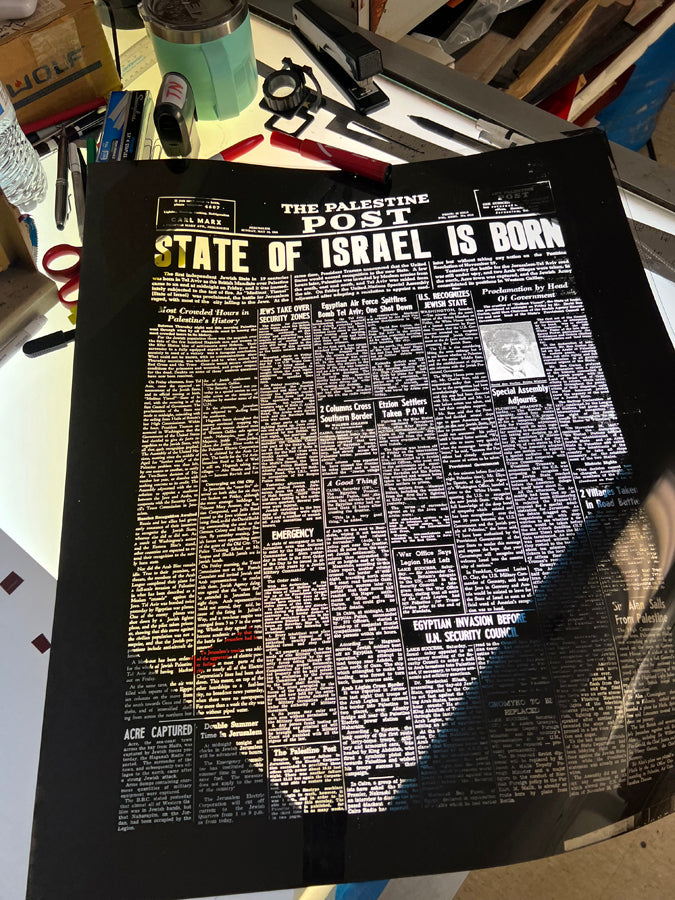

The magnesium sheet is then thoroughly inspected again, and significant time is spent physically gouging any bits of unwanted metal, as those would result in spots of ink on the sheet. The plate is then mounted on a specially-crafted block of cherry wood and sent to a proofing press to check the image quality on paper.

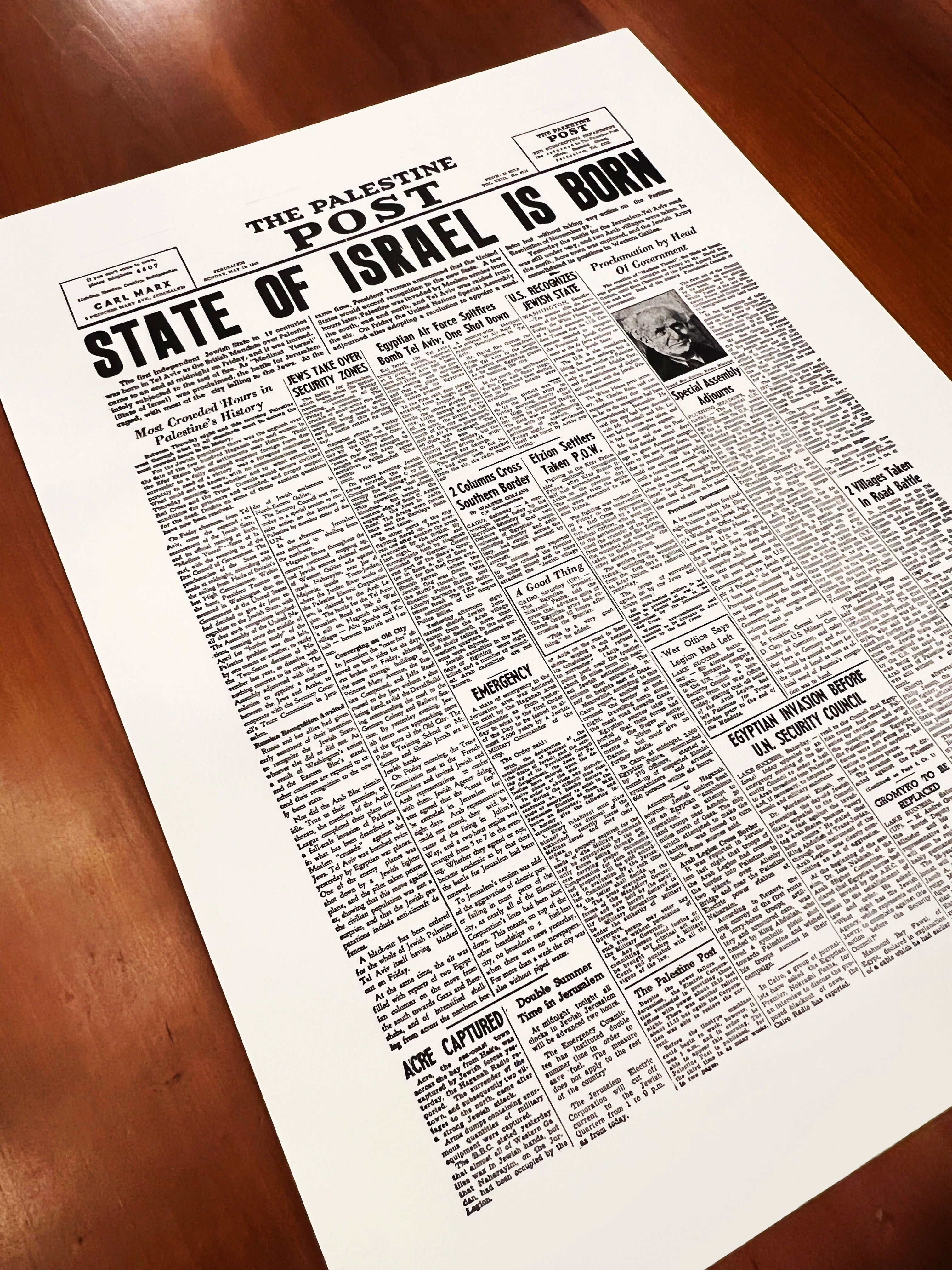

Large (26” x 40”) sheets of 100% cotton paper are procured and cut down to the actual print size, and prepared for the final step of printing.

The mounted plate is then locked into place on the press, inked up by hand, and test “makeready” sheets are printed. These are used to check the position of the image on the sheet, the print quality, the ink coverage, and the depth of the impression. Adjustments are made until the first print is approved.

As the print run begins, each sheet of paper is carefully hand-mounted on a drum, and old-fashioned muscle power is used to roll the paper over the plate. Each individual print is then examined and set aside to dry. In order to achieve consistency, the plate is re-inked approximately every 8 to 10 prints. This is, after all, a hand-made process, and each print has its own unique qualities.

Finally, each Limited Edition print is hand embossed and numbered to ensure its authenticity and value.

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.